Large Scale Kernel Methods - Scaling Up Kernel SVM via Low-rank Linearization

- Yang WANG

- Emmanuel DOUMARD

Problèmatique kernel SVM :

\

- φ(x) est toujours inconnu et potentiellement en dimension infinie.

- Dans ce cas, nous ne pouvons que résoudre le problème dans sa forme duale

- Le temps d’apprentissage est alors en $\mathcal{O}(n^2)$ ou $\mathcal{O}(n^3)$

- Idée: trouver une feature map en dimension finie $\hat{φ}(x) ∈ R^c$ telle que

$⟨\hat{φ}(x), \hat{φ}(x′)⟩ ≈ K(x, x′)$

- On peut résoudre le problème dans sa forme primale avec $w \in R^c$ et $b \in R^2$

- Le temps d’apprentissage en $\mathcal{O}(n)$. ([Shalev-Shwartz et al., 2011])

import numpy as np

from scipy import linalg

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.style.use('ggplot')

import seaborn as sns

from IPython.display import set_matplotlib_formats

set_matplotlib_formats('retina')

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.datasets import load_svmlight_file

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

%load_ext line_profiler

Chargement et partitionnement des données

###############################################################################

# Requires file ijcnn1.dat.gz to be present in the directory

dataset_path = 'ijcnn1.dat'

ijcnn1 = load_svmlight_file(dataset_path)

X = ijcnn1[0].todense()

y = ijcnn1[1]

###############################################################################

# Extract features

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X[:60000, :], y[:60000],

train_size=20000, random_state=42)

scaler = StandardScaler()

X_train = scaler.fit_transform(X_train)

X_test = scaler.transform(X_test)

n1, p = X_train.shape

n2 = X_test.shape[0]

print("Nombre d'exemples d'apprentissage:", n1)

print("Nombre d'exemples de test:", n2)

print("Nombre de features:", p)

Nombre d'exemples d'apprentissage: 20000

Nombre d'exemples de test: 40000

Nombre de features: 22

Question 1

On va fitter nos données d’apprentissage avec un SVM linéaire et un SVM non-linéaire (noyau Gaussien) pour comparer leur score de prédiction ainsi que le temps de calcul nécessaire à l’apprentissage et à la prédiction.

from sklearn.svm import SVC, LinearSVC

from time import time

print("Fitting SVC rbf on %d samples..." % X_train.shape[0])

t0 = time()

# TODO

clf = SVC(kernel='rbf')

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

print("done in %0.3fs" % (time() - t0))

print("Predicting with SVC rbf on %d samples..." % X_test.shape[0])

t1 = time()

# TODO

y_pred = clf.predict(X_test)

print("done in %0.3fs" % (time() - t1))

timing_kernel = time() - t0

accuracy_kernel = accuracy_score(y_test, y_pred)

print("classification accuracy: %0.3f" % accuracy_kernel)

# TODO same for LinearSVC

print("Fitting linear SVC on %d samples..." % X_train.shape[0])

t3 = time()

# TODO

clfL = LinearSVC(dual=False)

clfL.fit(X_train, y_train)

print("done in %0.3fs" % (time() - t3))

print("Predicting with linear SVC on %d samples..." % X_test.shape[0])

t4 = time()

# TODO

y_predL = clfL.predict(X_test)

print("done in %0.3fs" % (time() - t4))

timing_linear = time() - t3

accuracy_linear = accuracy_score(y_test, y_predL)

print("classification accuracy: %0.3f" % accuracy_linear)

print("Predicting with linear SVC with dual problem on %d samples..." %

X_test.shape[0])

print("The linear SVM takes %0.3fs to fit and predict while the kernel SVM takes %0.3fs to fit and predict" %

(timing_linear, timing_kernel))

print("The linear SVM has an accuracy of %0.3f while the kernel SVM has an accuracy of %0.3f" %

(accuracy_linear, accuracy_kernel))

Fitting SVC rbf on 20000 samples...

done in 4.006s

Predicting with SVC rbf on 40000 samples...

done in 4.398s

classification accuracy: 0.980

Fitting linear SVC on 20000 samples...

done in 0.415s

Predicting with linear SVC on 40000 samples...

done in 0.005s

classification accuracy: 0.917

Predicting with linear SVC with dual problem on 40000 samples...

The linear SVM takes 0.420s to fit and predict while the kernel SVM takes 8.404s to fit and predict

The linear SVM has an accuracy of 0.917 while the kernel SVM has an accuracy of 0.980

On remarque que le SVM avec noyau $O(n^2)$ est plus long à calculer mais aussi plus précis pour la prédiction que le SVM sans noyau en forme primale $O(n)$.

# We test with dual form SVM, normaly its complexity = O(n*n)

print("Fitting linear SVC on %d samples..." % X_train.shape[0])

t5 = time()

# TODO

clfL = LinearSVC(dual=True)

clfL.fit(X_train,y_train)

print("done in %0.3fs" % (time() - t5))

print("Predicting with linear SVC on %d samples..." % X_test.shape[0])

t6 = time()

# TODO

y_predL = clfL.predict(X_test)

print("done in %0.3fs" % (time() - t6))

timing_linear2 = time() - t3

accuracy_linear = accuracy_score(y_test,y_predL)

print("classification accuracy: %0.3f" % accuracy_linear)

Fitting linear SVC on 20000 samples...

done in 3.600s

Predicting with linear SVC on 40000 samples...

done in 0.002s

classification accuracy: 0.917

//anaconda3/lib/python3.7/site-packages/sklearn/svm/base.py:929: ConvergenceWarning: Liblinear failed to converge, increase the number of iterations.

"the number of iterations.", ConvergenceWarning)

On remarque que le SVM avec forme duale est plus long à calculer. $O(n^2)$

Question 2

On code une fonction qui calcule la meilleure approximation de rang $k$.

from scipy.sparse.linalg import svds

from scipy.linalg import svd

def rank_trunc(gram_mat, k, fast=True):

"""

k-th order approximation of the Gram Matrix G.

Parameters

----------

gram_mat : array, shape (n_samples, n_samples)

the Gram matrix

k : int

the order approximation

fast : bool

use svd (if False) or svds (if True).

Return

------

gram_mat_k : array, shape (n_samples, n_samples)

The rank k Gram matrix.

"""

if fast:

#svds return directly the ndarray s of singular values, shape=(k,) k as a parameter

u, s, vt = svds(gram_mat, k=k)

#np.diag transform ndarray into a diagonal matrix

gram_mat_k = np.dot(np.dot(u,np.diag(s)),vt)

else:

#svd return all singular values in a array s, sorted in non-increasing order. Of shape (K,), with K = min(M, N).

u, s, vt = svd(gram_mat)

gram_mat_k = np.linalg.multi_dot([u[:,:k],np.diag(s[:k]),vt[:k,:]])

return gram_mat_k

Question 3

On applique cette fonction sur la matrice décrite dans le sujet de TP.

p = 200

r_noise = 100

r_signal = 20

intensity = 50

rng = np.random.RandomState(42)

X_noise = rng.randn(r_noise, p)

X_signal = rng.randn(r_signal, p)

gram_signal = np.dot(X_noise.T, X_noise) + intensity * np.dot(X_signal.T,

X_signal)

n_ranks = 100

ranks = np.arange(1, n_ranks + 1)

timing_fast = np.zeros(n_ranks)

timing_slow = np.zeros(n_ranks)

rel_error = np.zeros(n_ranks)

for k, rank in enumerate(ranks):

#print(k, rank)

t0 = time()

gram_mat_k = rank_trunc(gram_signal, rank, fast=True)

timing_fast[k] = time() - t0

t0 = time()

gram_mat_k = rank_trunc(gram_signal, rank, fast=False)

timing_slow[k] = time() - t0

# TODO: compute relative error with Frobenius norm

rel_error[k] = np.linalg.norm(gram_mat_k - gram_signal,ord='fro')/np.linalg.norm(gram_signal,ord='fro')

###############################################################################

# Display

sns.set()

f, axes = plt.subplots(ncols=1, nrows=2, figsize=(10, 6))

ax1, ax2 = axes.ravel()

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_fast, '-', label='fast')

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_slow, '-', label='slow')

ax1.legend()

ax1.set_xlabel('Rank')

ax1.set_ylabel('Time')

ax2.plot(ranks, rel_error, '-')

ax2.plot(ranks, rel_error0, '-')

ax2.set_xlabel('Rank')

ax2.set_ylabel('Relative Error')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

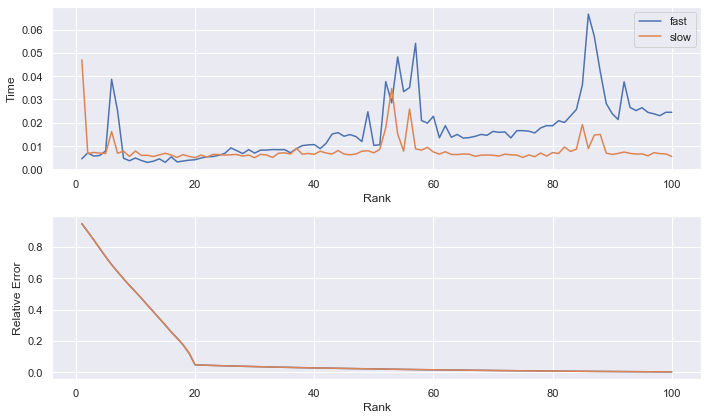

La version “rapide” ne semble plus rapide que pour les faibles valeurs de k, tandis que la version “lente” semble de temps constant peut importe la valeur de k.

La version “rapide” calcule seulement avec les k premiers valeurs singulières, quand $k « min(n,m)$, elle retourne beaucoup moins de choses que l’autre, elle est donc plus “rapide”. Alors que la version “lente” calculer toujours toutes les valeurs singulières.

L’erreur relative semble diminuer rapidement jusqu’à $k = 20$, puis elle diminue très lentement jusqu’à être presque nulle pour $k = 199$.

p = 200

r_noise = 100

r_signal = 20

intensity = 50

rng = np.random.RandomState(42)

X_noise = rng.randn(r_noise, p)

X_signal = rng.randn(r_signal, p)

gram_signal = np.dot(X_noise.T, X_noise) + intensity * np.dot(X_signal.T,

X_signal)

n_ranks = 199

ranks = np.arange(1, n_ranks + 1)

timing_fast = np.zeros(n_ranks)

timing_slow = np.zeros(n_ranks)

rel_error = np.zeros(n_ranks)

for k, rank in enumerate(ranks):

#print(k, rank)

t0 = time()

gram_mat_k = rank_trunc(gram_signal, rank, fast=True)

timing_fast[k] = time() - t0

t0 = time()

gram_mat_k = rank_trunc(gram_signal, rank, fast=False)

timing_slow[k] = time() - t0

# TODO: compute relative error with Frobenius norm

rel_error[k] = np.linalg.norm(gram_mat_k - gram_signal,ord='fro')/np.linalg.norm(gram_signal,ord='fro')

# Display

sns.set()

f, axes = plt.subplots(ncols=1, nrows=2, figsize=(10, 6))

ax1, ax2 = axes.ravel()

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_fast, '-', label='fast')

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_slow, '-', label='slow')

ax1.legend()

ax1.set_xlabel('Rank')

ax1.set_ylabel('Time')

ax2.plot(ranks, rel_error, '-')

ax2.set_xlabel('Rank')

ax2.set_ylabel('Relative Error')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

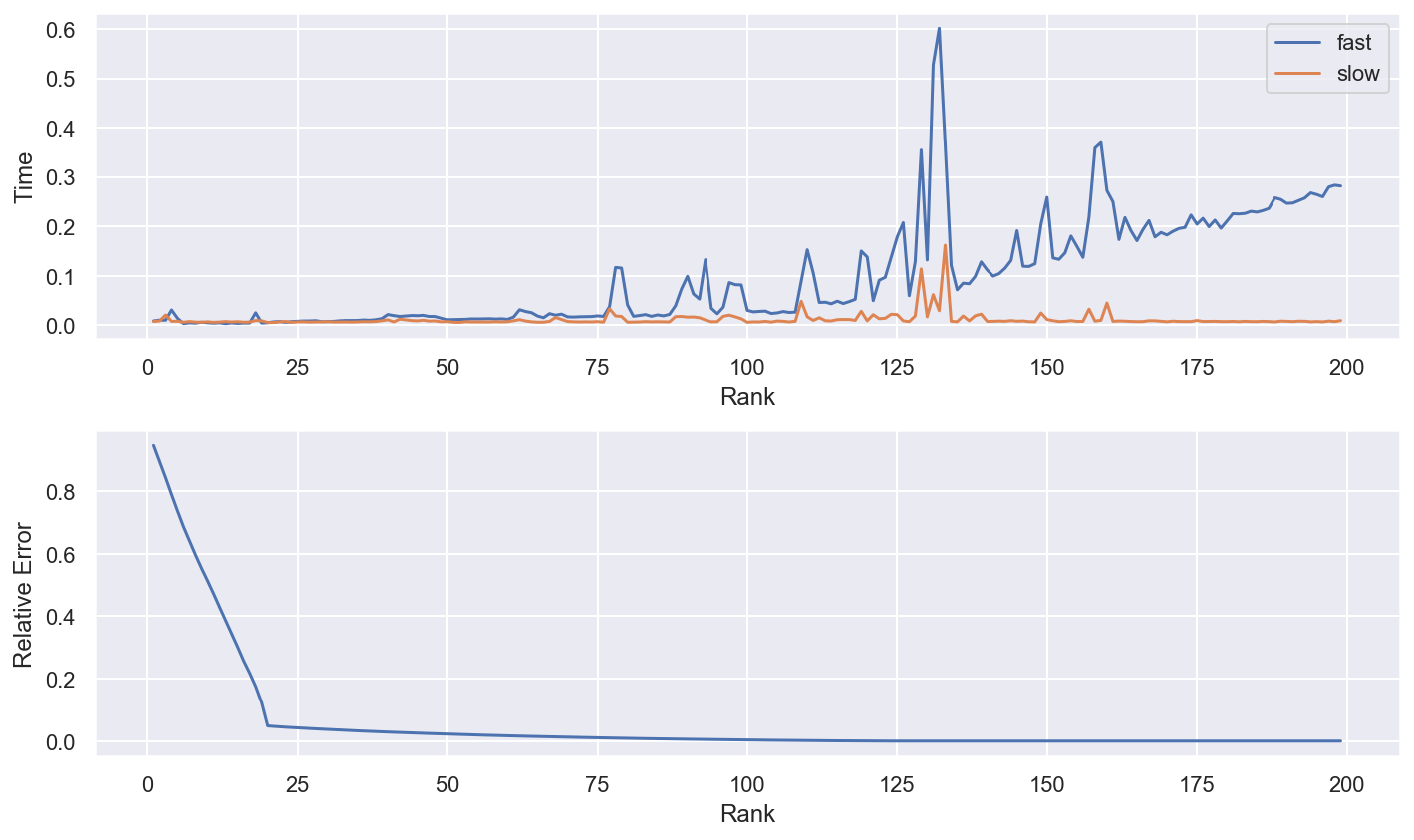

A partir de k=125, la version “rapide” deviens beaucoup moins efficace, cette version est plus adaptée aux matrices sparce avec un $k « min(n,m)$, car il ne retourne qu’un ndarray de valeurs singulières de taille (k,).

Question 4

On va implémenter l’algorithme de Random Kernel Features pour le noyau Gaussien.

def random_features(X_train, X_test, gamma, c=300, seed=44, Laplace=False):

"""Compute random kernel features

Parameters

----------

X_train : array, shape (n_samples1, n_features)

The train samples.

X_test : array, shape (n_samples2, n_features)

The test samples.

gamma : float

The Gaussian kernel parameter

c : int

The number of components

seed : int

The seed for random number generation

Return

------

X_new_train : array, shape (n_samples1, c)

The new train samples.

X_new_test : array, shape (n_samples2, c)

The new test samples.

"""

if Laplace==False:

#Gaussian kernel

rng = np.random.RandomState(seed)

n_samples, n_features = X_train.shape

W = rng.normal(0,np.sqrt(2*gamma),(n_features,c))

b = rng.uniform(0,2*np.pi,(1,c))

X_new_train = np.zeros((X_train.shape[0],c))

X_new_test = np.zeros((X_test.shape[0],c))

for i in range(X_train.shape[0]):

X_new_train[i,:] = np.sqrt(2.0/c)*np.cos(np.dot(X_train[i,:],W) + b)

for i in range(X_test.shape[0]):

X_new_test[i,:] = np.sqrt(2.0/c)*np.cos(np.dot(X_test[i,:],W) + b)

else:

#Laplace Kernel

rng = np.random.RandomState(seed)

n_samples, n_features = X_train.shape

#W in Cauchy distribution

W = rng.standard_cauchy((n_features,c))

b = rng.uniform(0,2*np.pi,(1,c))

X_new_train = np.zeros((X_train.shape[0],c))

X_new_test = np.zeros((X_test.shape[0],c))

for i in range(X_train.shape[0]):

X_new_train[i,:] = np.sqrt(2.0/c)*np.cos(np.dot(X_train[i,:],W) + b)

for i in range(X_test.shape[0]):

X_new_test[i,:] = np.sqrt(2.0/c)*np.cos(np.dot(X_test[i,:],W) + b)

return X_new_train, X_new_test

Question 5

On va maintenant appliquer cette méthode avec $c=300$.

n_samples, n_features = X_train.shape

n_samples_test, _ = X_test.shape

gamma = 1. / n_features

t0 = time()

Z_train, Z_test = random_features(X_train, X_test, gamma, c=300, seed=44)

print("Fitting SVC linear on %d samples..." % n_samples)

clf = LinearSVC(dual=False)

clf.fit(Z_train, y_train)

print("done in %0.3fs" % (time() - t0))

print("Predicting with SVC linear on %d samples..." % n_samples_test)

t1 = time()

accuracy_RKF = clf.score(Z_test, y_test)

print("done in %0.3fs" % (time() - t1))

timing_RKF = time() - t0

print("classification accuracy: %0.3f" % accuracy_RKF)

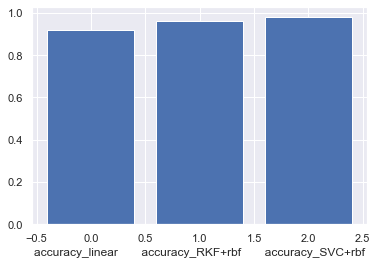

print("\nAccuracy :")

print("Linear : \t%0.3f" % accuracy_linear)

print("RKF+rbf: \t%0.3f" % accuracy_RKF)

print("SVC+rbf: \t%0.3f" % accuracy_kernel)

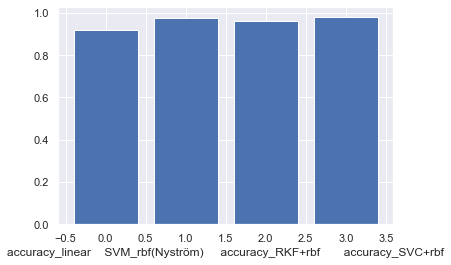

plt.xlabel("accuracy_linear accuracy_RKF+rbf accuracy_SVC+rbf")

plt.bar(range(3),(accuracy_linear,accuracy_RKF,accuracy_kernel))

plt.show()

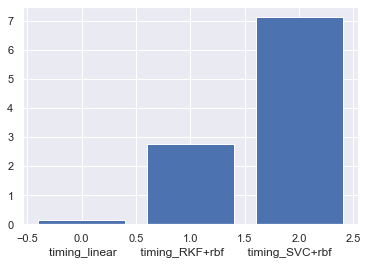

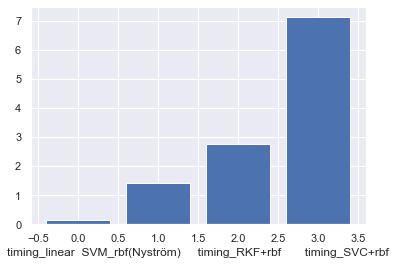

print("\nTime :")

print("Linear : \t%0.3fs" % timing_linear)

print("RKF+rbf: \t%0.3fs" % timing_RKF)

print("SVC+rbf: \t%0.3fs" % timing_kernel)

plt.xlabel("timing_linear timing_RKF+rbf timing_SVC+rbf")

plt.bar(range(3),(timing_linear,timing_RKF,timing_kernel))

Fitting SVC linear on 20000 samples...

done in 2.733s

Predicting with SVC linear on 40000 samples...

done in 0.019s

classification accuracy: 0.963

Accuracy :

Linear : 0.917

RKF+rbf: 0.963

SVC+rbf: 0.980

Time :

Linear : 0.129s

RKF+rbf: 2.753s

SVC+rbf: 7.120s

<BarContainer object of 3 artists>

En temps comme en précision, cette méthode RKF s’inscrit entre les deux considérées à la question 1 : elle est plus lente mais plus précise que la méthode sans noyau, et plus rapide mais moins précise que la méthode avec noyau.

Question 6

On implémente la méthode de Nyström.

from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import rbf_kernel

def nystrom(X_train, X_test, gamma, c=500, k=200, seed=44):

"""Compute nystrom kernel approximation

Parameters

----------

X_train : array, shape (n_samples1, n_features)

The train samples.

X_test : array, shape (n_samples2, n_features)

The test samples.

gamma : float

The Gaussian kernel parameter

c : int

The number of points to sample for the approximation

k : int

The number of components

seed : int

The seed for random number generation

Return

------

X_new_train : array, shape (n_samples1, c)

The new train samples.

X_new_test : array, shape (n_samples2, c)

The new test samples.

"""

rng = np.random.RandomState(seed)

n_samples = X_train.shape[0]

# Generates a random sample with replacement

idx = rng.choice(n_samples, c, replace=1)

X_train_idx = X_train[idx, :]

W = rbf_kernel(X_train_idx, X_train_idx, gamma=gamma)

#the best rand k approximation

Vk, sigma_k, Vkt = svd(W)

Vk = Vk[:, :k]

Vkt = Vkt[:k, :]

sigma_k = sigma_k[:k]

M_k = np.dot(Vk, np.diag(1/np.sqrt(sigma_k)))

C_train = rbf_kernel(X_train, X_train_idx, gamma=gamma)

C_test = rbf_kernel(X_test, X_train_idx, gamma=gamma)

X_new_train = np.dot(C_train, M_k)

X_new_test = np.dot(C_test, M_k)

return X_new_train, X_new_test

Question 7

On va maintenant appliquer cette méthode également avec $c=500$ et $k=300$

Z_train, Z_test = nystrom(X_train, X_test, gamma, c=500, k=300, seed=44)

print("Fitting SVC linear on %d samples..." % n_samples)

t0 = time()

clf = LinearSVC(dual=False)

clf.fit(Z_train, y_train)

print("done in %0.3fs" % (time() - t0))

print("Predicting with SVC linear on %d samples..." % n_samples_test)

t1 = time()

accuracy_nystrom = clf.score(Z_test, y_test)

print("done in %0.3fs" % (time() - t1))

timing_nystrom = time() - t0

print("classification accuracy: %0.3f" % accuracy_nystrom)

print("\nAccuracy :")

print("LinearSVM : \t%0.3f" % accuracy_linear)

print("SVM_rbf(Nyström) : \t%0.3f" % accuracy_nystrom)

print("SVM_rbf(RKF) : \t%0.3f" % accuracy_RKF)

print("SVM_rbf_Kernel : \t%0.3f" % accuracy_kernel)

plt.xlabel("accuracy_linear SVM_rbf(Nyström) accuracy_RKF+rbf accuracy_SVC+rbf")

plt.bar(range(4),(accuracy_linear,accuracy_nystrom,accuracy_RKF,accuracy_kernel))

plt.show()

print("\nTime :")

print("LinearSV : \t%0.3fs" % timing_linear)

print("SVM_rbf(Nyström) : \t%0.3fs" % timing_nystrom)

print("SVM_rbf(RKF) : \t%0.3fs" % timing_RKF)

print("SVM_rbf_Kernel : \t%0.3fs" % timing_kernel)

plt.xlabel("timing_linear SVM_rbf(Nyström) timing_RKF+rbf timing_SVC+rbf")

plt.bar(range(4),(timing_linear,timing_nystrom,timing_RKF,timing_kernel))

Fitting SVC linear on 20000 samples...

done in 1.395s

Predicting with SVC linear on 40000 samples...

done in 0.018s

classification accuracy: 0.976

Accuracy :

LinearSVM : 0.917

SVM_rbf(Nyström) : 0.976

SVM_rbf(RKF) : 0.963

SVM_rbf_Kernel : 0.980

Time :

LinearSV : 0.129s

SVM_rbf(Nyström) : 1.414s

SVM_rbf(RKF) : 2.753s

SVM_rbf_Kernel : 7.120s

<BarContainer object of 4 artists>

La méthode de l’approximation de Nyström semble efficace puisqu’elle est plus rapide que RKF tout en étant plus efficace que celle-ci. Elle atteint une précision comparable à celle de la méthode à noyau.

Avec le même numbre de samples (features/columns), Nystöm a tendance d’avoir meilleur performance que RKF, alors qu’en général, RKF est moins cher à générer ( pas besoins de décomposition spectrale ni inversion de matrice)

Question 8

On va maintenant réaliser une synthèse des performances des RKF et de Nystrom pour un ensemble de paramètres.

ranks = np.arange(20, 600, 50)

n_ranks = len(ranks)

timing_rkf = np.zeros(n_ranks)

timing_nystrom = np.zeros(n_ranks)

timing_rkf_laplace = np.zeros(n_ranks)

accuracy_nystrom = np.zeros(n_ranks)

accuracy_rkf = np.zeros(n_ranks)

accuracy_rkf_laplace = np.zeros(n_ranks)

# TODO: compute time and prediction scores for RKF and Nystrom with respect to c

# put results in timing_rkf, timing_nystrom, accuracy_rkf, accuracy_nystrom

print("Training SVMs for various values of c...")

for i, c in enumerate(ranks):

t0 = time()

Z_train, Z_test = random_features(X_train, X_test, gamma, c=c, seed=44)

clf = LinearSVC(dual=False)

clf.fit(Z_train, y_train)

accuracy_rkf[i] = clf.score(Z_test, y_test)

timing_rkf[i] = time() - t0

t1 = time()

Z_train, Z_test = nystrom(X_train, X_test, gamma, c=c, k=c-10, seed=44)

clf = LinearSVC(dual=False)

clf.fit(Z_train, y_train)

accuracy_nystrom[i] = clf.score(Z_test, y_test)

timing_nystrom[i] = time() - t1

t2 = time()

Z_train, Z_test = random_features(

X_train, X_test, gamma, c=c, seed=44, Laplace=True)

clf = LinearSVC(dual=False)

clf.fit(Z_train, y_train)

accuracy_rkf_laplace[i] = clf.score(Z_test, y_test)

timing_rkf_laplace[i] = time() - t0

Training SVMs for various values of c...

###############################################################################

# Display bis

sns.set()

f, axes = plt.subplots(ncols=1, nrows=2, figsize=(13,10))

ax1, ax2 = axes.ravel()

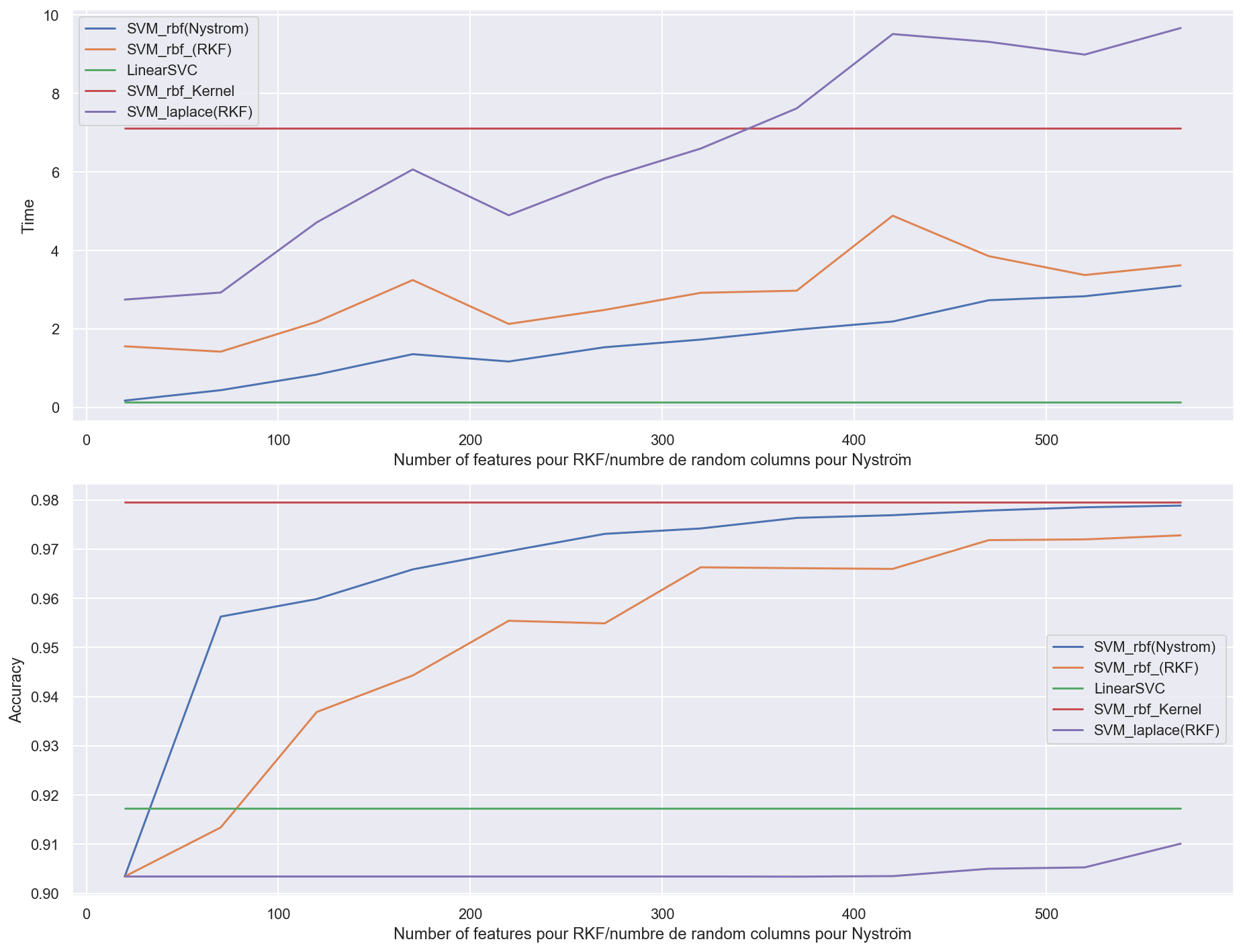

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_nystrom, '-', label='SVM_rbf(Nystrom)')

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_rkf, '-', label='SVM_rbf_(RKF)')

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_linear * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='LinearSVC')

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_kernel * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='SVM_rbf_Kernel')

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_rkf_laplace * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='SVM_laplace(RKF)')

ax1.legend()

ax1.set_xlabel('Number of features pour RKF/numbre de random columns pour Nyström')

ax1.set_ylabel('Time')

ax2.plot(ranks, accuracy_nystrom, '-', label='SVM_rbf(Nystrom)')

ax2.plot(ranks, accuracy_rkf, '-', label='SVM_rbf_(RKF)')

ax2.plot(ranks, accuracy_linear * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='LinearSVC')

ax2.plot(ranks, accuracy_kernel * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='SVM_rbf_Kernel')

ax2.plot(ranks, accuracy_rkf_laplace * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='SVM_laplace(RKF)')

ax2.set_xlabel('Number of features pour RKF/numbre de random columns pour Nyström')

ax2.set_ylabel('Accuracy')

ax2.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

-

Accuracy:

-

En termes d’accuracy, les méthodes Nystrom et RKF convergent toutes les deux vers le vrai SVM à noyau avec $O(1/\sqrt{c})$ convergence. (avec c le nombre de random features pour RKF, le nombre de random columns pour Nyström)

-

la méthode par approximation de Nystrom converge plus rapidement vers la méthode par SVM à noyau (vers c = 500). En effet, Nyström peut avoir O(1/c) convergence quand eigengap de G est large [Yang et al., 2012]

-

Globalement, on observe que la méthode Nystrom est meilleure que RKF, et ce peu importe le nombre de features considérées. Cependant, la guarantee d’approximation de Nyström est adaptive aux données, alors que RKF est indépendant aux données.

-

-

Time:

-

Tandis qu’au niveau du temps de calcul, Nyström reste bien plus rapide même avec c = 500 (où elle est entre trois et quatre fois plus rapide sur l’échantillon considéré).

-

Nyström et RKF sont plus rapides que le SVM à noyau, sauf Nyström avec noyau Laplacian quand ‘c’ est grand.

-

Bonus : Laplace(Nyström)

Laplace RKF déjà dans function RKF.

from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import laplacian_kernel

def laplace(X_train, X_test, gamma, c=500, k=200, seed=44):

"""Compute nystrom kernel approximation

Parameters

----------

X_train : array, shape (n_samples1, n_features)

The train samples.

X_test : array, shape (n_samples2, n_features)

The test samples.

gamma : float

The Gaussian kernel parameter

c : int

The number of points to sample for the approximation

k : int

The number of components

seed : int

The seed for random number generation

Return

------

X_new_train : array, shape (n_samples1, c)

The new train samples.

X_new_test : array, shape (n_samples2, c)

The new test samples.

"""

rng = np.random.RandomState(seed)

n_samples = X_train.shape[0]

idx = rng.choice(n_samples, c)

X_train_idx = X_train[idx, :]

W = laplacian_kernel(X_train_idx, X_train_idx, gamma=gamma)

Vk, sigma_k, Vkt = svd(W)

Vk = Vk[:,:k]

Vkt = Vkt[:k,:]

sigma_k=sigma_k[:k]

M_k = np.dot(Vk,np.diag(1/np.sqrt(sigma_k)))

Ctrain = laplacian_kernel(X_train,X_train_idx)

Ctest = laplacian_kernel(X_test,X_train_idx)

X_new_train = np.dot(Ctrain,M_k)

X_new_test = np.dot(Ctest,M_k)

return X_new_train, X_new_test

ranks = np.arange(20, 600, 50)

n_ranks = len(ranks)

timing_rkf = np.zeros(n_ranks)

timing_nystrom = np.zeros(n_ranks)

timing_laplace = np.zeros(n_ranks)

timing_Nyströme_stack = np.zeros(n_ranks)

accuracy_nystrom = np.zeros(n_ranks)

accuracy_rkf = np.zeros(n_ranks)

accuracy_laplace = np.zeros(n_ranks)

accuracy_Nyströme_stack = np.zeros(n_ranks)

print("Training SVMs for various values of c...")

for i, c in enumerate(ranks):

#print(i, c)

t0 = time()

Z_train, Z_test = random_features(X_train, X_test, gamma, c=c, seed=44)

clf = LinearSVC(dual=False)

clf.fit(Z_train, y_train)

accuracy_rkf[i] = clf.score(Z_test, y_test)

timing_rkf[i] = time() - t0

t1 = time()

Z_train, Z_test = nystrom(X_train, X_test, gamma, c=c, k=c-10, seed=44)

clf = LinearSVC(dual=False)

clf.fit(Z_train, y_train)

accuracy_nystrom[i] = clf.score(Z_test, y_test)

timing_nystrom[i] = time() - t1

t2 = time()

Z_train, Z_test = laplace(X_train, X_test, gamma, c=c, k=c-10, seed=44)

clf = LinearSVC(dual=False)

clf.fit(Z_train, y_train)

accuracy_laplace[i] = clf.score(Z_test, y_test)

timing_laplace[i] = time() - t2

t3 = time()

Z_train1, Z_test1 = nystrom(X_train, X_test, gamma, c=c, k=c-10, seed=44)

Z_train2, Z_test2 = laplace(X_train, X_test, gamma, c=c, k=c-10, seed=44)

Z_train = np.hstack((Z_train1, Z_train2))

Z_test = np.hstack((Z_test1, Z_test2))

clf = LinearSVC(dual=False)

clf.fit(Z_train, y_train)

accuracy_Nyströme_stack[i] = clf.score(Z_test, y_test)

timing_Nyströme_stack[i] = time() - t3

# TODO: compute time and prediction scores for RKF and Nystrom with respect to c

# put results in timing_rkf, timing_nystrom, accuracy_rkf, accuracy_nystrom

Training SVMs for various values of c...

###############################################################################

# Display bis

sns.set()

f, axes = plt.subplots(ncols=1, nrows=2, figsize=(13,10))

ax1, ax2 = axes.ravel()

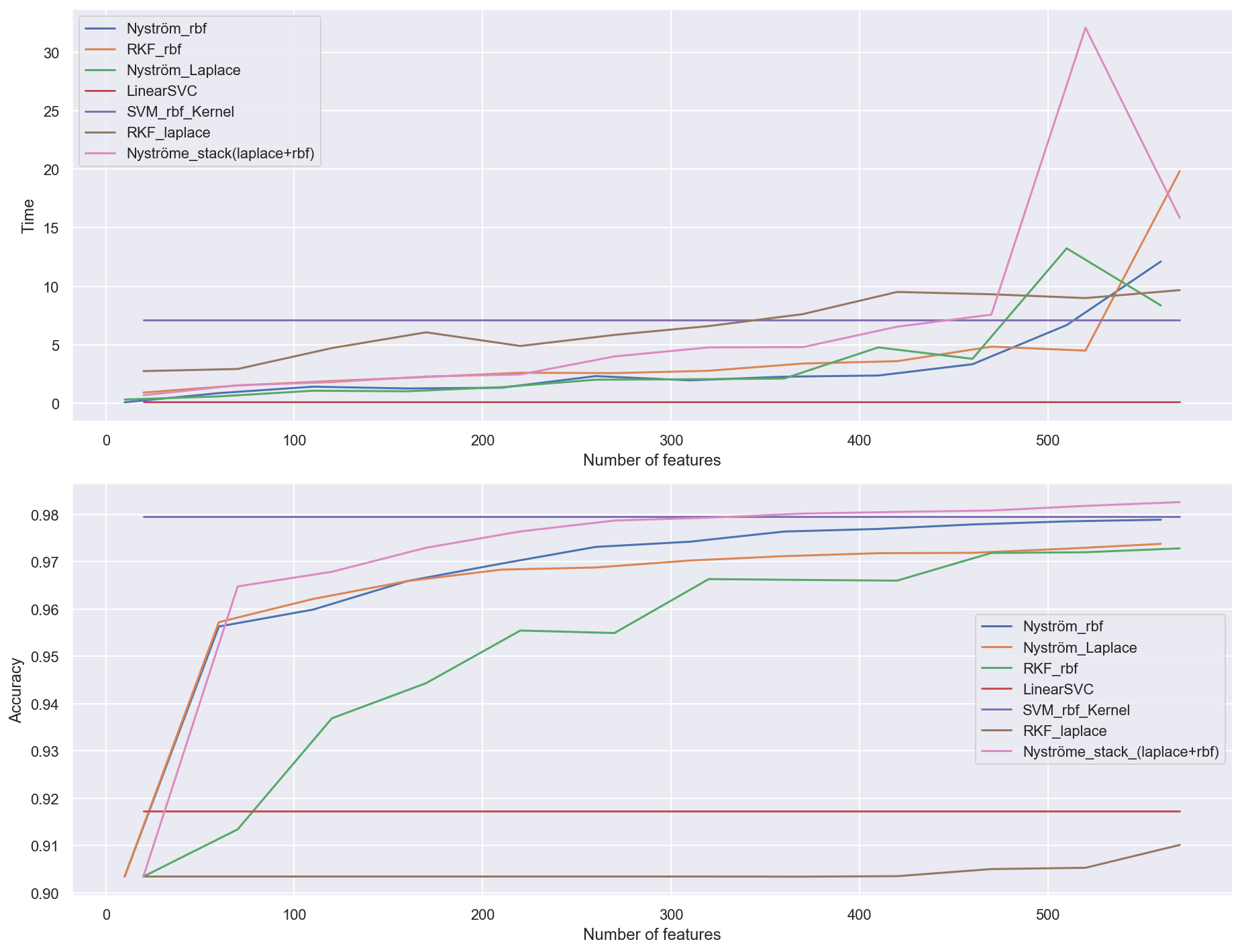

ax1.plot(ranks-10, timing_nystrom, '-', label='Nyström_rbf')

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_rkf, '-', label='RKF_rbf')

ax1.plot(ranks-10, timing_laplace, '-', label='Nyström_Laplace')

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_linear * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='LinearSVC')

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_kernel * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='SVM_rbf_Kernel')

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_rkf_laplace * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='RKF_laplace')

ax1.plot(ranks, timing_Nyströme_stack * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='Nyströme_stack(laplace+rbf)')

ax1.set_xlabel('Number of features')

ax1.set_ylabel('Time')

ax1.legend()

ax2.plot(ranks-10, accuracy_nystrom, '-', label='Nyström_rbf')

ax2.plot(ranks-10, accuracy_laplace, '-', label='Nyström_Laplace')

ax2.plot(ranks, accuracy_rkf, '-', label='RKF_rbf')

ax2.plot(ranks, accuracy_linear * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='LinearSVC')

ax2.plot(ranks, accuracy_kernel * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='SVM_rbf_Kernel')

ax2.plot(ranks, accuracy_rkf_laplace * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='RKF_laplace')

ax2.plot(ranks, accuracy_Nyströme_stack * np.ones(n_ranks), '-', label='Nyströme_stack_(laplace+rbf)')

ax2.set_xlabel('Number of features')

ax2.set_ylabel('Accuracy')

ax2.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

-

Time:

-

Avec le même noyau, Nyström est plus rapide que la technique de RKF et SVC kernel. Les temps d’excution d’Nyström avec noyau gaussien et noyau laplacien sont quasiment identiques. Enfin, Sklearn SVC API ne fournie pas de Laplace kernel, nous ne pouvons pas comparer avec Laplace(RKF/Nyström).

-

Avec le feature map en grand dimension, les méthodes d’approximation de noyaux ont tendance à prendre plus de temps que le SVM à noyau normal.

-

Le stacking de Nyströme_stack_(laplace+rbf) est le plus lent puisqu’on calcule les deux features map et stack avec numpy.

-

-

Accuracy:

-

Avec notre dataset, la méthode de Nyström converge plus vite la méthode RKF avec les deux types de noyaux (Gaussian et Laplace).

-

Le stacking des 2 noyaux Gaussian(Nyström) et Laplace(Nyström) converge le plus vite. En effet, la combinaison de features obtenus avec noyeau Gaussian(Nyström) et Laplace(Nyström) permets de faciliter l’apprentissage du modèle, qui donne le meilleur performance.

-

-

Trade-off

- Avec 300 features, nous avons une très bonne précision alors que nous avons une nette accéleration computationelle en calculant d’abord les features puis en les applicants à un sur classifieur linéaire.

Conclusion

\

Nous avons testé

- les features aléatoires (RKF) dont les produits scalaire approximent les noyaux Gaussien et Laplacien

- les features obtenues par approximation de la matrice du noyau (Nyström)

Nous démontrons que ces features sont des outils puissants et économiques pour faire du large-scale supervised learning.

Nous montrons empiriquement que fournir ces features comme entrées d’un classifier standard comme SVM produit des résultats competitifs en termes de précision et de temps d’apprentissage.

Il est à noter que la combinaison de ces features donne également de bonnes performances